Period Poverty: Reusable pad to school girls rescue

Shammah said governments should prioritise promoting girl-child education through the distribution of pads, particularly in rural areas and urban suburbs.;

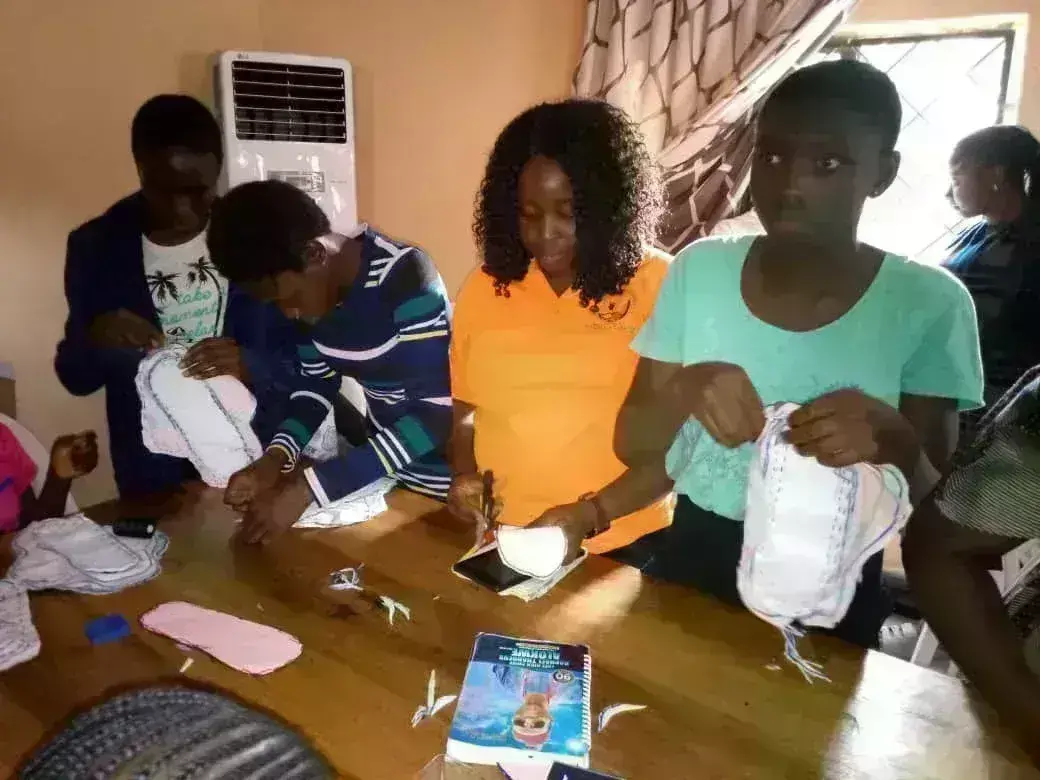

Training of school girls in making reusable pads organises by the Plateau Chapter of NAWOJ in Jos

In Abuja, North Central Nigeria, the girls of Junior Secondary School (JSS) Wuse, Zone 2, are excited that they have learned a new skill that would ease their access to education amidst the numerous challenges the girl-child confronts.

Training of young girls of Junior Secondary School (JSS) Wuse, Zone 2, on the making of reusable organised by FOWGI

One of such challenges is period poverty, or the lack of access to safe, hygienic menstrual products. It also involves a lack of access to sanitation services and menstrual hygiene education.

Baek Caleb, in an article, shed light on the pervasive issue of period poverty in Nigeria, affecting over 37 million girls and women who cannot afford essential menstrual hygiene products.

The article, entitled Millions of Nigerian Females in Period Poverty, was published in an Elsevier journal.

In spite of the gravity of the situation, they say, the crisis remains largely unaddressed and normalised within Nigerian society.

“The escalating cost of sanitary pads over the past 15 years has exacerbated the problem, pushing a vital necessity out of reach for a significant portion of the population’’, he advised.

This period of poverty is not peculiar to Nigeria.

According to a study, 500 million people in the U.S. lack access to menstrual products and hygiene facilities, while 16.9 million people who menstruate in the US are living in poverty.

“Two-thirds of the 16.9 million low-income women in the US could not afford menstrual products in the past year, with a half of this needing to choose between menstrual products and food," say Janet Michel and other scholars in a study.

The study entitled Poverty Period: “Why It Should Be Everybody’s Business" is featured in the Journal of Health Reports.

Gyer Hembafan, 17, from Benue, is one of the 30 young girls who were taught by an NGO, Focusing on Women and Girls Initiative (FOWGI) for Positive Change, how to make reusable pads.

She was brought to Abuja by her aunty in 2020 for better life opportunities, particularly in education.

The aim is also to bring relief to her mother, a widow based in Makurdi who is struggling to take care of her other two sisters.

Hembafan says: “In our village, we use cloth during our menstrual period, and we do not dispose of it properly.

She explained that the discomfort of using clothes discourages many girls from attending school in her village during their periods.

According to UNESCO, in Sub-Saharan Africa, one in 10 girls misses school during her menstrual cycle, which equates to up to 20 percent of a school year.

Ecstatic, Hembafan says she looks forward to visiting her village in Makurdi to share what she has learned in Abuja.

“I will teach them how to make reusable pads and how to dispose of them properly by wrapping them in a bag before throwing them in a bin,“ she said.

A sigh of relief has also come to her aunt with this development, especially considering the increasing economic challenges in the country.

She will no longer need to buy the disposable pads, the cheapest of which costs about N600 in the market for just seven to eight pieces.

Experts say sanitary pads should be changed every eight hours, meaning a minimum of two packs are needed for a menstrual period of five days.

She says her aunt has other needs to handle, and she is happy that this one is off her list. Moreover, she is privileged to access quality education in the city compared to her peers in the village.

Also, Sarah Edunjobi, 12, from the same school, is eager to share her knowledge of making reusable pads with her sister when she returns home from school.

She introduced her sister to it and received positive feedback, along with a request to be taught.

Edunjobi says her mother has been supporting her by purchasing the materials she needs to produce the pads and encouraging her to also sell them.

Similarly, in the city of Jos, in Plateau, Blessing Pam, 13, from Government Secondary School, was among the 30 beneficiaries of the reusable pad training organised by the Nigeria Association of Women Journalists (NAWOJ) in November 2023.

She is always scared of staining herself during her period and feels sorry for her mother, who bears the burden of buying sanitary towels for her every month from her sales of gruel (kunu), while also caring for her other four siblings.

She expresses her desire to make reusable pads and sell them if given the opportunity. She believes that the government should give them for free to schoolgirls.

Period poverty has made women use unconventional materials during their periods.

A report indicates that the use of crude, improvised materials such as scraps of old clothing, pieces of foam mattress, toilet paper, leaves, and banana fibres for monthly periods prevents them from engaging in their daily activities, including attending school.

Menstruation is a natural process that typically begins in girls between the ages of 10 and 14.

It is expected to be embraced by females as a source of pride, but reports indicate that some girls develop anxiety toward their period due to being unable to afford proper menstrual products.

Unfortunately, due to poverty, this natural phenomenon has caused many girls to be out of school or to skip going to school.

According to UNICEF, one in every five out-of-school children in the world is in Nigeria. The report stated that states in the North-East and North-West have female primary net attendance rates of 47.7 percent and 47.3 percent, respectively, indicating that more than half of the girls are not in school.

Experts say that although the reasons for poor attendance could be numerous, providing sustainable measures to address the menstrual challenge period would greatly impact their ability to confidently participate fully in school activities.

Girl Child Education (GEM) International, an NGO, has continuously donated reusable sanitary towels to schoolgirls in northern Nigeria.

Its director, Mrs. Keturah Shammah, has identified period poverty as a factor that makes girls absent from school.

“In one of our surveys in a public school in Jos South Local Government Area, between 10 and 12 percent of the girls normally miss school every day. The one we had recently missed school by 20 percent because most of them do not have access to a sanitary pad.

“So if they are menstruating, they will have to stay at home. Anytime we go to a school, we will have not less than 10 girls absent because of menstrual issues,“ she said.

Shammah said governments should prioritise promoting girl-child education through the distribution of pads, particularly in rural areas and urban suburbs.

The advocate also urged governments to be intentional in formulating policies that provided for sustainable schemes for the distribution of sanitary towels and should consider providing reusable pads for schoolgirls.

Similarly, Mrs. Nene Dung, Chairperson NAWOJ, Plateau chapter, said they sponsored the training of 30 girls in the making of reusable pads to stem the increasing number of out-of-school girls, particularly in the North.

She urged the government to partner with organisations such as NAWOJ and similar associations to train girls on making reusable pads and commended the Adolescent Girls Initiative for Learning and Empowerment (AGILE) World Bank project.

She urged state governments to create similar programmes through the offices of their first ladies and their ministries of women affairs to promote girl-child education.

Mrs. Rifkatu Bello, the Executive Director of FOWGI, another NGO, believes that to provide a sustainable solution, the reusable pad initiative should be adopted by governments at all levels.

She said achieving SDG 4 of inclusive and equitable quality education by 2030 requires training girls on how to make reusable pads to address period poverty.

While stakeholders urge the government and NGOs to adopt the training of schoolgirls on reusable pads and their free distribution, similar to the free distribution of condoms, to mitigate the spread of HIV/AIDS,.

It is hoped that the AGILE project will incorporate the training of girls on reusables and their distribution as a sustainable measure.

Benefits of reusable for periods

Source: TRADE TO AID reusable sanitary pads

Girl child advocates say that menstruation should not hinder girl child education due to poverty.

Therefore, critical stakeholders must be intentional about creating an enabling environment for the girl child, ensuring she does not see this natural biological process as a barrier to a brighter future.